Shellfish (oysters, clams, mussels) pose the greatest risk to be contaminated with norovirus; there is no way to detect a contaminated oyster, clam, or mussel from a safe one.

Because shellfish are filter feeders and concentrate virus particles present in their environment, shellfish become contaminated when their waters are polluted with raw sewage.

2018 Contaminated Oyster Norovirus Outbreak

A 2018 multi-state outbreak of Norovirus illnesses was associated with contaminated oysters harvested in Baynes Sound, British Columbia, Canada, and were distributed to AK, CA, FL, HI, IL, MA, NY, and WA. The contamination was determined to be human sewage in the marine environment.

According to the the Public Health Agency of Canada, a total of 176 cases of gastrointestinal illness linked to oyster consumption were reported in three provinces: British Columbia (137), Alberta (14), and Ontario (25). No deaths were reported. Individuals became sick between mid-March and mid-April 2018.

The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) reported approximately 100 individuals reported illness after they consumed raw British Columbia oysters sold by restaurants and retailers throughout the state.

Although the outbreak appears to be over, this outbreak is a reminder that oysters are a known risk for causing food-related illness if consumed as a raw product.

Oysters can cause food-related illness if eaten raw, particularly in people with compromised immune systems. Food contaminated with noroviruses may look, smell, and taste normal.

Norovirus infection can be prevented through attention to proper sanitation and cooking procedures.

What is norovirus?

Norovirus is a highly contagious virus that can cause viral gastroenteritis, often called “food poisoning” or the “stomach flu.” Eating raw or partially cooked shellfish can cause norovirus infection.

How do shellfish become contaminated with norovirus?

Norovirus makes its way into the marine environment through untreated human sewage (poop) and vomit. This may come from leaky septic systems, faulty waste water treatment plants, boaters, or beach-goers. Shellfish are filter feeders, which means they filter seawater through their bodies to get food floating in the water. When norovirus particles are in the water, shellfish can accumulate the virus in their bodies.

What types of shellfish are affected?

All bivalve shellfish such as clams, geoducks, mussels, scallops, and oysters can transmit norovirus. Illness outbreaks are most often linked to oysters because they are commonly eaten raw.

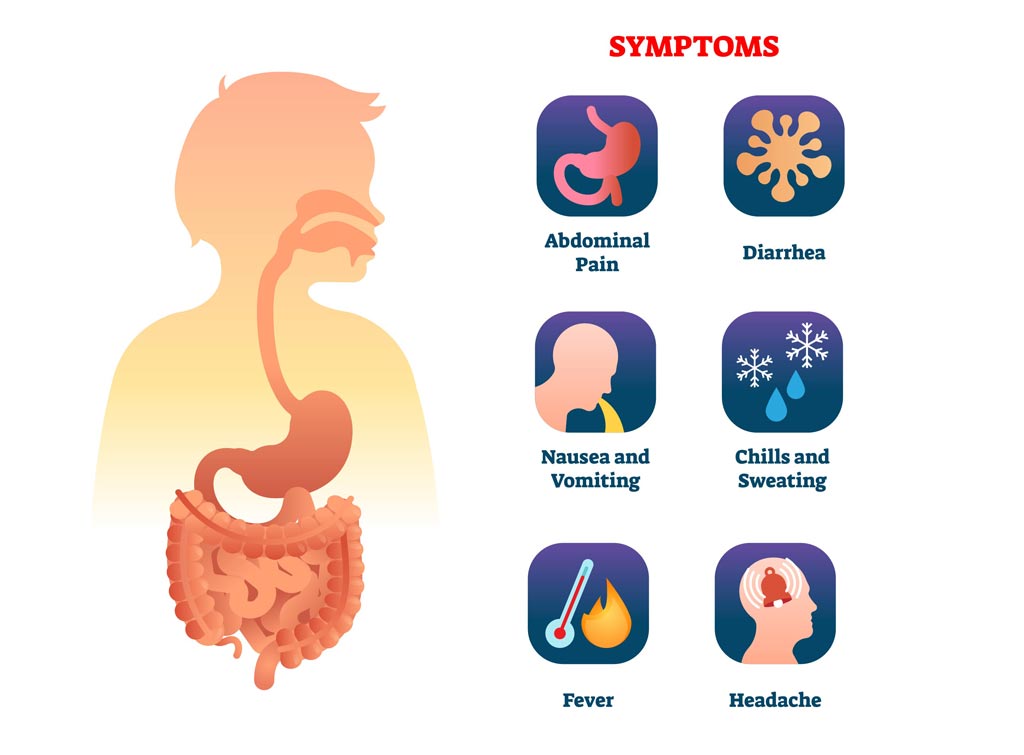

What are the symptoms of norovirus?

The most common symptoms of norovirus are stomach pain, projectile vomiting, and severe diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, headache, and body aches. Some people can be infected with norovirus and have no symptoms. Good hygiene and hand washing, especially after using the bathroom and when handling food, are important to help limit the spread of norovirus.

How soon do symptoms appear?

Symptoms usually appear 24-48 hours after being exposed to the virus. Sometimes symptoms appear as early as 12 hours after exposure. Most people recover in 1 to 3 days.

Who is most at risk?

Anyone can get norovirus. Young children, the elderly, and anyone who already has other illnesses may experience longer, more serious illness, and rarely, death.

People who eat raw oysters or undercooked shellfish are at higher risk of a norovirus illness. Norovirus persists longer in colder marine water and we tend to see more shellfish-related norovirus illnesses in November through March.

Cooking Raw Shellfish to Enure Safety

To ensure proper food safety, raw shellfish must be cooked to an internal temperature of at least 145°F or 15 seconds. Since it is often impractical to use a food thermometer to check the temperature of cooked shellfish, here are some tips and recommended ways to cook shellfish safely:

- Shucked shellfish (clams, mussels and oysters without shells) become plump and opaque when cooked thoroughly and the edges of the oysters start to curl. The FDA suggests boiling shucked oysters for 3 minutes, frying them in oil at 375°F for 10 minutes, or baking them at 450°F for 10 minutes.

- Clams, mussels and oysters in the shell will open when cooked. The FDA suggests steaming oysters for 4 to 9 minutes or boiling them for 3 to 5 minutes after they open.

- Scallops turn milky white or opaque and firm. Depending on size, scallops take 3 to 4 minutes to cook thoroughly.

- Boiled lobster turns bright red. Allow 5 to 6 minutes – start timing the lobster when the water comes back to a full boil.

- Shrimp turn pink and firm. Depending on the size, it takes from 3 to 5 minutes to boil or steam 1 pound of medium size shrimp in the shell.

Additional Precautions

Norovirus can also be transmitted by ill individuals and are able to survive relatively high levels of chlorine and varying temperatures. Cleaning and disinfecting practices are the key to preventing further illnesses in your home.

- Thoroughly clean contaminated surfaces, and disinfect using chlorine bleach, especially after an episode of illness.

- After vomiting or diarrhea, immediately remove and wash clothing or linens that may be contaminated with the virus (use hot water and soap).

- If you have been diagnosed with norovirus illness or any other gastrointestinal illness, do not prepare food or pour drinks for other people while you have symptoms, and for the first 48 hours after you recover.

What is Vibrio and Vibriosis?

One of the infections you might get from eating raw oysters is caused by some types of Vibrio, bacteria that occur naturally in coastal waters where oysters live. When someone eats raw or undercooked oysters that contain bacteria or exposes a wound to seawater that contains Vibrio, he or she can get an illness called vibriosis.

Vibriosis causes about 80,000 illnesses and 100 deaths in the United States every year. Most of these illnesses happen from May through October when water temperatures are warmer. However, you can get sick from eating raw or undercooked oysters during any month of the year, and raw oysters from typically colder waters also can cause vibriosis.

What are the symptoms of vibriosis?

Most Vibrio infections from oysters, such as Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection, result in only diarrhea and vomiting. However, people with a Vibrio vulnificus infection can get very sick. As many as 1 in 3 people with a V. vulnificus infectiondie. This is because the infection can result in bloodstream infections, severe blistering skin lesions, and limb amputations. If you develop symptoms of vibriosis, tell your medical provider if you recently ate or handled raw shellfish.

Who is more likely to get vibriosis?

Anyone can get sick from vibriosis, but you may be more likely to get an infection or severe complications if you:

- Have liver disease, alcoholism, cancer, diabetes, HIV, or thalassemia.

- Receive immune-suppressing therapy for the treatment of disease, such as for cancer.

- Have an iron overload disease, such as hemochromatosis.

- Take medicine to lower stomach acid levels, such as Nexium and Pepcid.

- Have had recent stomach surgery.

How do people get vibriosis?

Most people become infected by eating raw or undercooked shellfish, particularly oysters. Some people get infected through an open wound when swimming or wading in brackish or salt water.

How can I stay safe?

Follow these tips to reduce your chances of getting an infection when eating or handling shellfish and other seafood:

- Don’t eat raw or undercooked oysters or other shellfish. Fully cook them before eating, and only order fully cooked oysters at restaurants. Hot sauce and lemon juice don’t kill Vibrio bacteria and neither does alcohol.

- Some oysters are treated for safety after they are harvested. This treatment can reduce levels of vibrios in the oyster but it does not remove all harmful germs. People who are more likely to get vibriosis should not eat any raw oysters.

- Separate cooked seafood from raw seafood and its juices to avoid cross contamination.

- Wash your hands with soap and water after handing raw seafood.

- Cover any wounds if they could come into contact with raw seafood or raw seafood juices or with brackish or salt water.

- Wash open wounds and cuts thoroughly with soap and water if they have been exposed to seawater or raw seafood or its juices.

Other Shellfish Diseases

Oysters are subject to other various diseases which can reduce harvests and severely deplete local populations. Disease control focuses on containing infections and breeding resistant strains, and is the subject of much ongoing research.

- “Dermo” is caused by a protozoan parasite (Perkinsus marinus). It is a prevalent pathogen, causes massive mortality, and poses a significant economic threat to the oyster industry. The disease is not a direct threat to humans consuming infected oysters. Dermo first appeared in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1950s, and until 1978 was believed to be caused by a fungus. While it is most serious in warmer waters, it has gradually spread up the east coast of the United States.

- Multinucleated sphere X (MSX) is caused by the protozoan Haplosporidium nelsoni, generally seen as a multinucleated Plasmodium. It is infectious and causes heavy mortality in the eastern oyster; survivors, however, develop resistance and can help propagate resistant populations. MSX is associated with high salinity and water temperatures. MSX was first noted in Delaware Bay in 1957, and is now found all up and down the East Coast of the United States. Evidence suggests it was brought to the US when Crassostrea gigas, a Japanese oyster variety, was introduced to Delaware Bay.

Tips for Cooking Oysters & Other Shellfish

Before cooking, throw out any shellfish with open shells.

For oysters in the shell, either:

- Boil until the shells open and continue boiling 3–5 more minutes, or

- Steam until the shells open and continue steaming for 4–9 more minutes.

Only eat shellfish that open during cooking. Throw out shellfish that do not open fully after cooking.

For shucked oysters, either:

- Boil for at least 3 minutes or until edges curl,

- Fry for at least 3 minutes at 375°F,

- Broil 3 inches from heat for 3 minutes, or

- Bake at 450° F for 10 minutes.

More information

- Take a look at CDC’s questions and answers about Vibrio and vibriosis

- Listen to CDC podcast on the dangers of eating raw oysters

- Be food safe – learn how you can protect yourself from food poisoning

- Read more guidance on FoodSafety.gov for preventing Vibrio infections

- Learn more about aquaculture: http://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/aquaculture/index.htm

- Learn more about Pacific and Eastern oysters from FishWatch: http://www.fishwatch.gov/profiles/search/oyster